Hurricane Posters and Cognizant Dissociative Voyeurism

Social media is news now, even when it doesn't have to be. How the act of digital voyeurism only gets more unsettling with each passing event.

We operate in this modern world by a few undeniable truths: people are constantly filming, people are constantly posting, and people are constantly scrolling. Boredom is the enemy, and the bar for keeping someone's attention for longer than three seconds is increasingly, and infinitely, challenging. I was thinking about this during Hurricane Milton, watching as micro-influencers and actual influencers across parts of Florida uploaded video after video of their decision to stay in evacuation zones during the hurricane, ensuring every second was captured. It was a clear window into the world of hyper opportunistic posting that seems to reflect the very foundational rot within our culture — and it was a reminder that as attention begets attention, it'll only get worse.

Now, in an effort to not group every person posting content about Hurricane Milton to their public Reels page into one cohort, and in an even more challenging attempt to not lump all Floridian behavior into a response to one story, I want to jot down the different types of content creators who seemed to gain traction. I do realize that not everyone posting about a situation they found themselves in is thinking about audience reach. The overarching groups basically included:

- helpful survivalists

- aspiring meteorologists

- recently new to Florida homeowners

- unfortunate tourists

- conspiracy theorists

- braggy wealthy influencers

- wannabe influencer opportunists

It’s the last couple of bullet points I really want to focus on. The first half of that list is people documenting their shitty luck in a situation they found themselves in. They’re likely thinking, as I would be if I posted to my friends on Instagram “holy fuck.” It was a public demonstration of what happened to them. The latter half of the list, however, isn’t trying to bring attention to their situation — they’re using a situation to bring attention to their accounts. Their videos were publicly documented stories of what they got from the hurricane — opportunity. These videos encapsulated the culmination of everything social media popularity promised any average Joe could have if they were willing to take on the risk of public ridicule for a few days. Memories fade, follower counts don’t.

Wannabe influencers (and this is the real group I’m talking about in this essay) weren’t trying to shine a light on something CNN wasn’t getting. In an attempt to try and see if anyone was feeling the same kind of dissociative voyeurism that I was sitting with during Hurricane Milton, I posted on Instagram. Irony, I know. But I wasn’t alone. Friends who used Instagram as a pastime, friends who used Instagram for work, and friends who were influencers all asked the same question: why does this one feel different from all the other events where influencers, wannabe creators, and normal people all flooded social media sites with their professional looking videos?

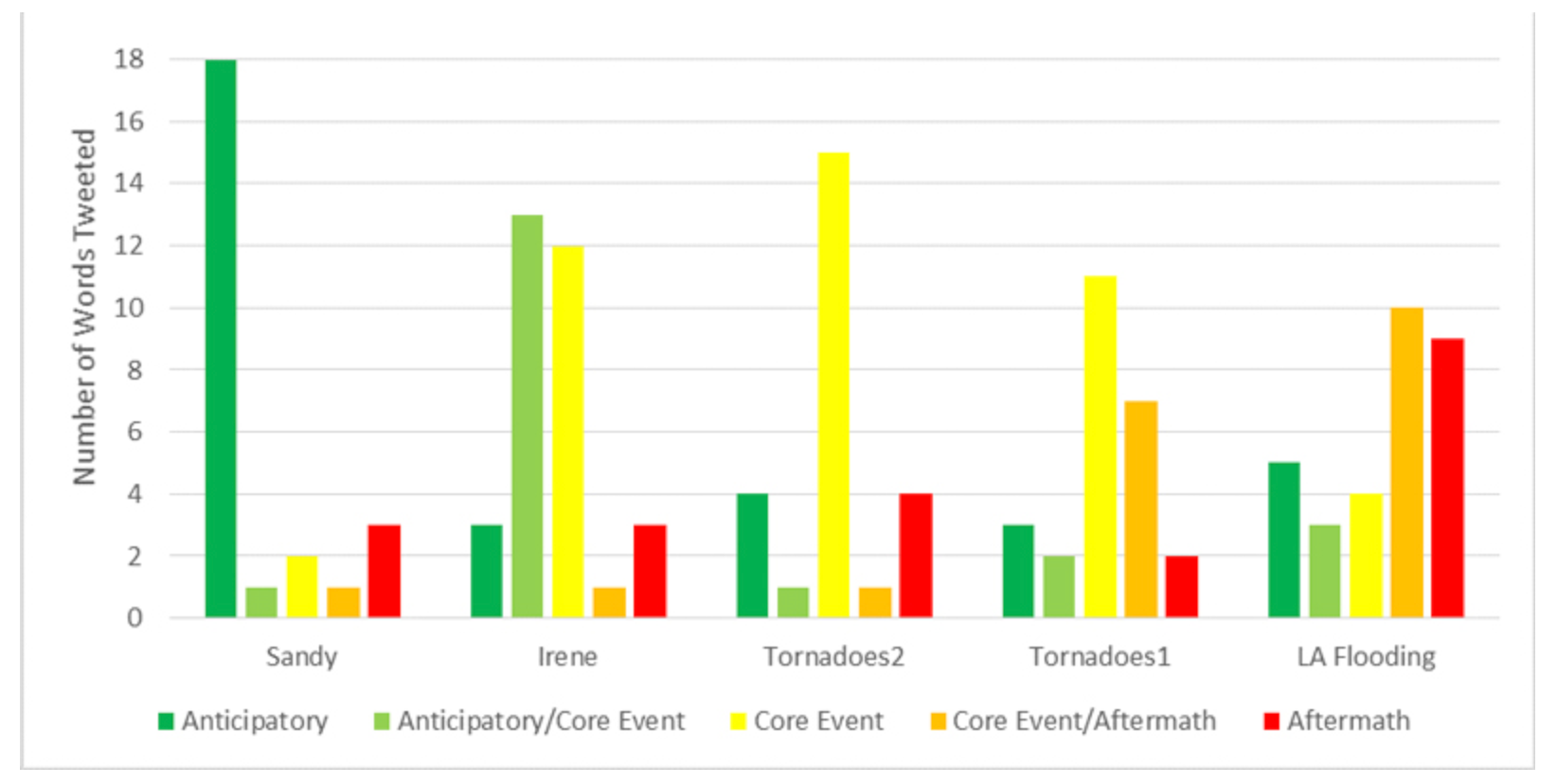

It's not like this is a new trend. Previous hurricanes (and other events) spurred anyone with an iPhone into action. A 2019 report from the University of Vermont looking at social media behavior around natural disasters on Twitter found that activity shifted depending on the type of disaster. Hurricanes saw higher levels of activity leading up to the event — similar to what we saw with Milton. Tornadoes, on the other hand, saw higher activity during or after the event, speaking to focused attention on rescue and clean up.

Perhaps the most interesting nugget of information was around the type of accounts that found traction: those with accounts between 100 and 200 followers saw higher engagement than those with millions of followers. This was in part due to being at the center of the event, but reiterates that even with the best intention (tweeting out information), the subconscious feedback from these types of events is that if you post, attention and larger social clout will follow.

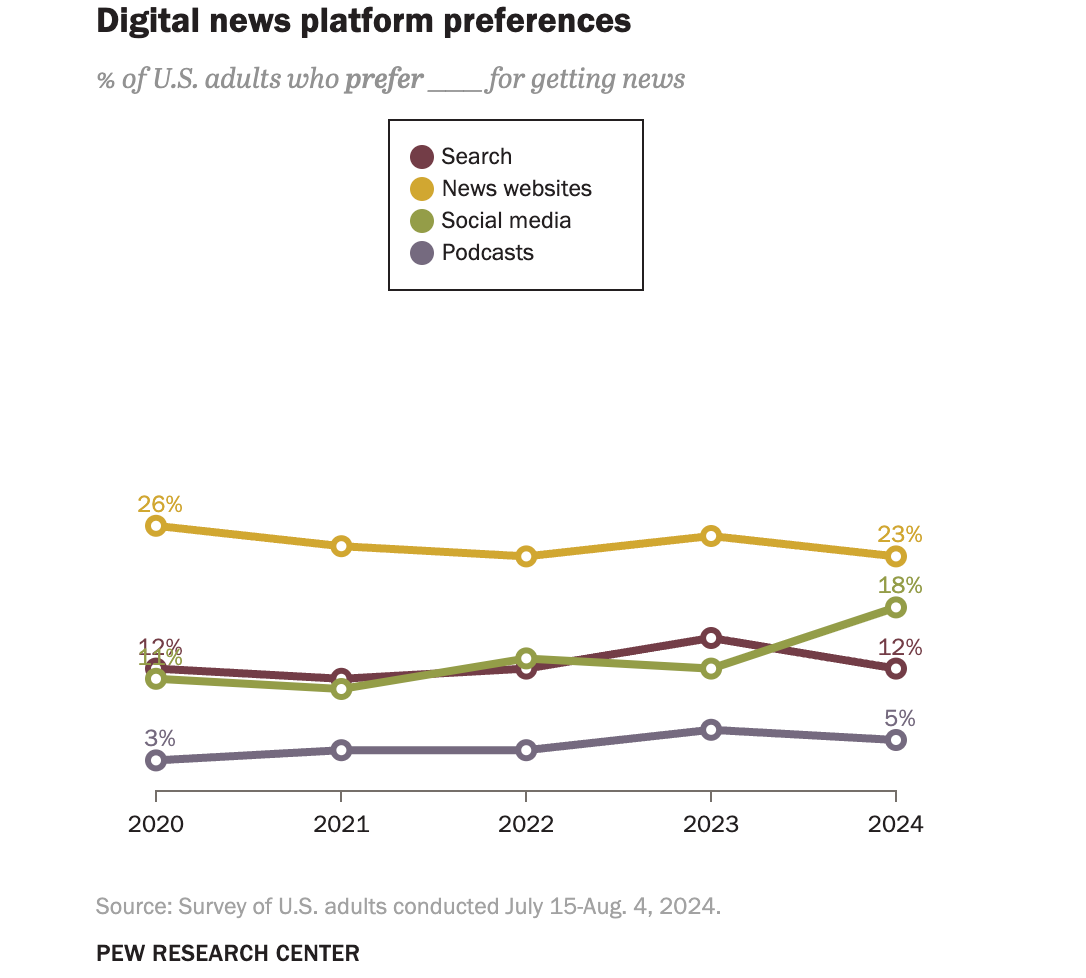

These data trends coincide with the direction that news production and news consumption is naturally moving toward. Younger audiences are turning to social video more and more for news than traditional cable or broadcast television stations. Nearly 60% of adults in the U.S. prefer getting their news from digital devices compared to the 32% who prefer television broadcasts, according to Pew’s September media habits report. Not to mention that news delivered via a news publication via digital distribution decreased from 25% to 22% between 2023 and 2024 amongst adults in the U.S. compared to social media, which increased from 12% to 18%.

Maybe the reality is this is how news will look going forward, but it’s partially why I wanted to broach this feeling of cognizant dissociative voyeurism. It’s a feeling that can only exist as the connections with strangers on our phone become more intimate — the quintessential parasocial relationship phenomena dialed up to a trillion. We saw our own dynamics reflected in the lives of strangers both hundred and thousands of miles away. At best, this ideally makes us more empathetic to causes we weren’t aware of before seeing a video. At worst, however, it makes us more competitive. Opportunity becomes the sole incentive factor for posting in those competitive settings, and our own private consumption habits reward those behaviors.

Breaking down the disconnect in one sentence effectively comes down to the situation behind a post. The chart above demonstrates that in events like a hurricane, the vast majority of activity comes from the anticipatory period of it making landfall. An immensely important part of that may extend from the ability to provide warning and evacuate. This is not an inescapable situation for all. State officials practically begged everyone to leave and, even with challenges like gas shortages and hotel costs, there was an option for most to go. Those who could leave and chose to hunker down and face a danger they could escape but opted not to in order to score attention for account growth is that precise rot that deeply unsettles me.

If I’m being bluntly honest with myself, part of the reason this dissociative voyeurism bothers me to the degree that it does is because I couldn’t stop scrolling. I watched those videos. I shared a couple with friends, thereby tricking Meta’s algorithms into thinking I wanted more of that type of content despite the context of each text boiling down to “I fucking hate this.” I spend my entire professional life reminding myself that people vote with their actions and their time. I scrolled. I shared. I spent hours on Instagram.

My friend Rebecca Jennings said something on X that I’m still chewing on. It was along the lines of, “They know they’ll never have this level of attention again.” It was followed by another friend of mine saying, half jokingly half seriously, that he wished he could be in Florida for the same reason that I am willing to bet thousands of other people wished the same thing: all those eyeballs on their content? All those eyeballs on them? That’s worth risking it all. The most cited dream job by kids in America under the age of 12 is a YouTuber/content creator. There are more than two billions hour of content posted every month. It's a job field with way too much supply and concentrated demand. High profile opportunity goes a long way in building a following.